Solstice happens once every 6 months – Summer Solstice in June and Winter Solstice in December. Midway between the two solstices we have equinoxes – Vernal Equinox in March and Autumnal Equinox in September.

The reason we have solstices (or equinoxes) is exactly the same as why we have seasons: the Earth’s axis is tilted with respect to the ecliptic (the Sun’s path across the sky). Thus, the celestial equator and the ecliptic do not lie on the same plane, but cross each other at an angle of 23.5 degrees. Hence, there will be two points on the celestial sphere where the ecliptic crosses the celestial equator and two instants during the year when the Sun is at its greatest angular distance from the celestial equator.

The intersection of the ecliptic and the celestial equator is known as the equinox. Since there are two intersections, there will be two equinoxes in a year: the Vernal (Spring) and the Autumnal Equinox. Spring and autumn officially begin at the instants of the vernal and autumnal equinox, respectively.

Another way of defining equinox is the time when the Sun crosses the celestial equator. When the Sun crosses the equator from south to north, it’s Vernal Equinox; when it crosses from north to south, it’s Autumnal Equinox.

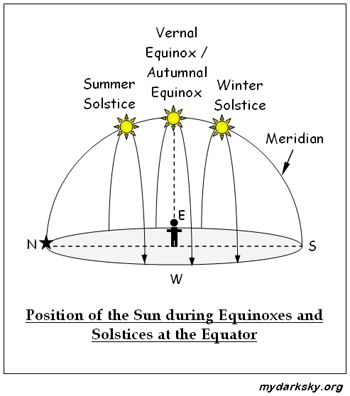

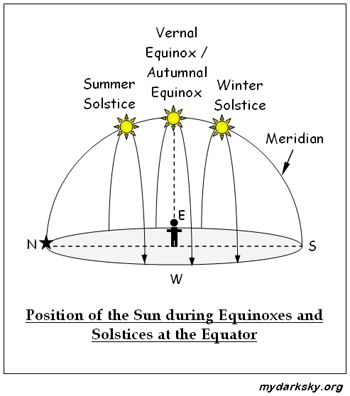

During equinoxes, the sun is directly over the Earth’s equator. At these times, the length of day and night are very nearly equal all over the world (equinox means “equal night”). On the equator, solar altitude (height of the Sun) reaches its maximum during the equinoxes (directly overhead or 90 degrees from the horizon). These are also the time when the Sun will rise exactly in the east and sets exactly in the west.

Solstice, on the other hand, happens at the two instants when the Sun is at its greatest angular distance from the celestial equator. During the course of a year, the apparent motion of the Sun as seen from Earth moves from south to north and back to south again. When the Sun changes direction from north to south or vice verse, it seems to stands still momentarily. This point of time is known as the solstice. Solstice is derived from Latin word “solstitium”; “sol” meaning Sun, and “sistere” meaning stand still.

Solstice, on the other hand, happens at the two instants when the Sun is at its greatest angular distance from the celestial equator. During the course of a year, the apparent motion of the Sun as seen from Earth moves from south to north and back to south again. When the Sun changes direction from north to south or vice verse, it seems to stands still momentarily. This point of time is known as the solstice. Solstice is derived from Latin word “solstitium”; “sol” meaning Sun, and “sistere” meaning stand still.

When the Sun is at its farthest north position from the celestial equator, it’s Summer Solstice; and when it is at the farthest south position, it’s Winter Solstice. Summer and winter officially begin at the instants of the summer and winter solstices, respectively.

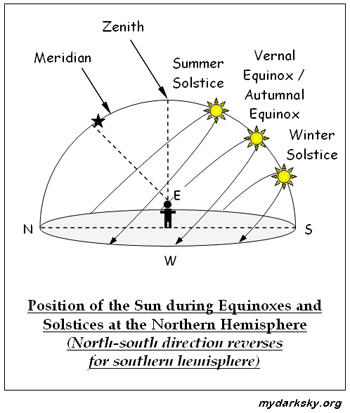

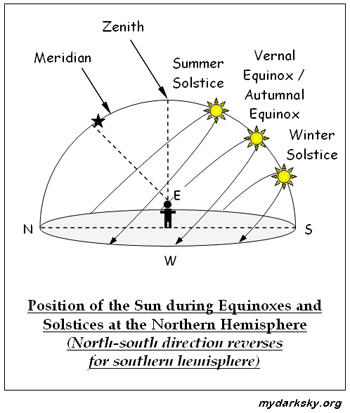

On the northern and southern hemisphere, the noontime Sun is highest in the sky during summer solstice and lowest in the sky during winter solstice. On the equator, however, we will only observe that the Sun is farthest north during summer solstice and farthest south during winter solstice. Solar altitude is the same during both summer and winter solstice (66.5 degrees from the horizon).

On the northern and southern hemisphere, the noontime Sun is highest in the sky during summer solstice and lowest in the sky during winter solstice. On the equator, however, we will only observe that the Sun is farthest north during summer solstice and farthest south during winter solstice. Solar altitude is the same during both summer and winter solstice (66.5 degrees from the horizon).

Astronomy Picture of the Day has a nice photo showing the different position of the Sun for the northern hemisphere. Just bear in mind that this photo does not reflect our situation at the equator. At the equator, the “middle band” Sun should be directly overhead (at the zenith), while the solstice Suns (“top band” and “bottom band” Sun) are the same distance above the horizon.

~~~~~

As the Earth moves around the Sun, we will see that the Sun position in the sky at the same time everyday keeps on changing, sometimes from north to south, and sometimes the other way round.

Refer to the diagram below, which is a typical diagram we use to learn about seasons in school, due to the axis tilt of our planet with respect to its orbit around the Sun, sometimes our Earth’s northern axis is tilted towards the Sun and sometimes the southern axis is tilted towards the Sun.

To visualise the Sun movement in the sky during the year, let’s start at the Vernal Equinox. On this day (more precisely, this point of time), the Sun shines on the equator. After this time, the Earth’s northern axis is tilted more and more towards the Sun, thus as seen from Earth, the Sun shifted its position towards the north. Then on Summer Solstice, the Sun will reach its farthest north position in the sky.

After the Summer Solstice, the cycle reverses; as the Earth continues to revolve around the Sun, the Earth’s northern axis is now tilted lesser and lesser towards the Sun. Thus as seen from Earth, the Sun’s position in the sky now will be shifted towards the south until it again shines on the equator on Autumnal Equinox.

After the Autumnal Equinox, the Sun will continue to moves south. This time, the Earth’s southern axis will be tilted more and more towards the Sun until it reaches a maximum tilt on Winter Solstice. On our sky, the Sun will be moving towards the south everyday until it reaches its farthest south position in the sky on Winter Solstice.

Then as the Earth moves towards the Vernal Equinox, our Earth’s southern axis tilt lesser and lesser towards the Sun – the Sun will now shift towards the north in our sky – until it again shines on the equator on Vernal Equinox and the cycle repeat itself.

Although we usually said that the Sun rises in the east and set in the west, in reality the Sun rises exactly due east and set exactly due west only two times in a year, that is during the equinoxes. Other times the Sun will either rise northeast and set northwest (from March to September), or rise southeast and set southwest (from September to March of the following year).

To observe this changing position of our Sun in the sky, try comparing its position everyday during sunrise or sunset against a reference point, for example against a building or a tree. Maybe you will not see any different in a day or two, but in weeks, you surely will notice that the Sun has moved.

Lastly, bear in mind that solstices and equinoxes only last an instant and not a whole day. In the case of the solstices, it’s the instant when the Sun “touches” its farthest north or south position and then “u-turn” back. It is the “u-turning” that makes the Sun seems to stands still momentarily. For the case of the equinoxes, it’s the instant when the Sun crosses the celestial equator. Having said that, these terms are usually loosely used to refer to the day within which the event occurs.

Posted in General Astro Talk

Tags: Equinox, Solstice

You must be logged in to post a comment.